Can You Grow Alpine Columbine in Full Sun? Unlocking the Secrets to a Blooming Mountain Beauty!

Ever admired the delicate, nodding blooms of alpine columbine and wondered if you could coax that same mountain magic into your own garden, even if your sunny spots get a bit too enthusiastic? The question of whether these charming wildflowers can truly thrive in full sun is a common one, and understanding their needs is key to unlocking their full potential and ensuring a vibrant display. Getting this right can mean the difference between a struggling plant and a cascade of exquisite, jewel-toned flowers, contributing to a more resilient and beautiful garden ecosystem.

Quick Answer Box

Yes, you can grow alpine columbine in full sun, but with crucial caveats. While they can tolerate full sun, especially in cooler climates, providing afternoon shade and ensuring consistently moist soil is vital for preventing stress and promoting robust flowering.

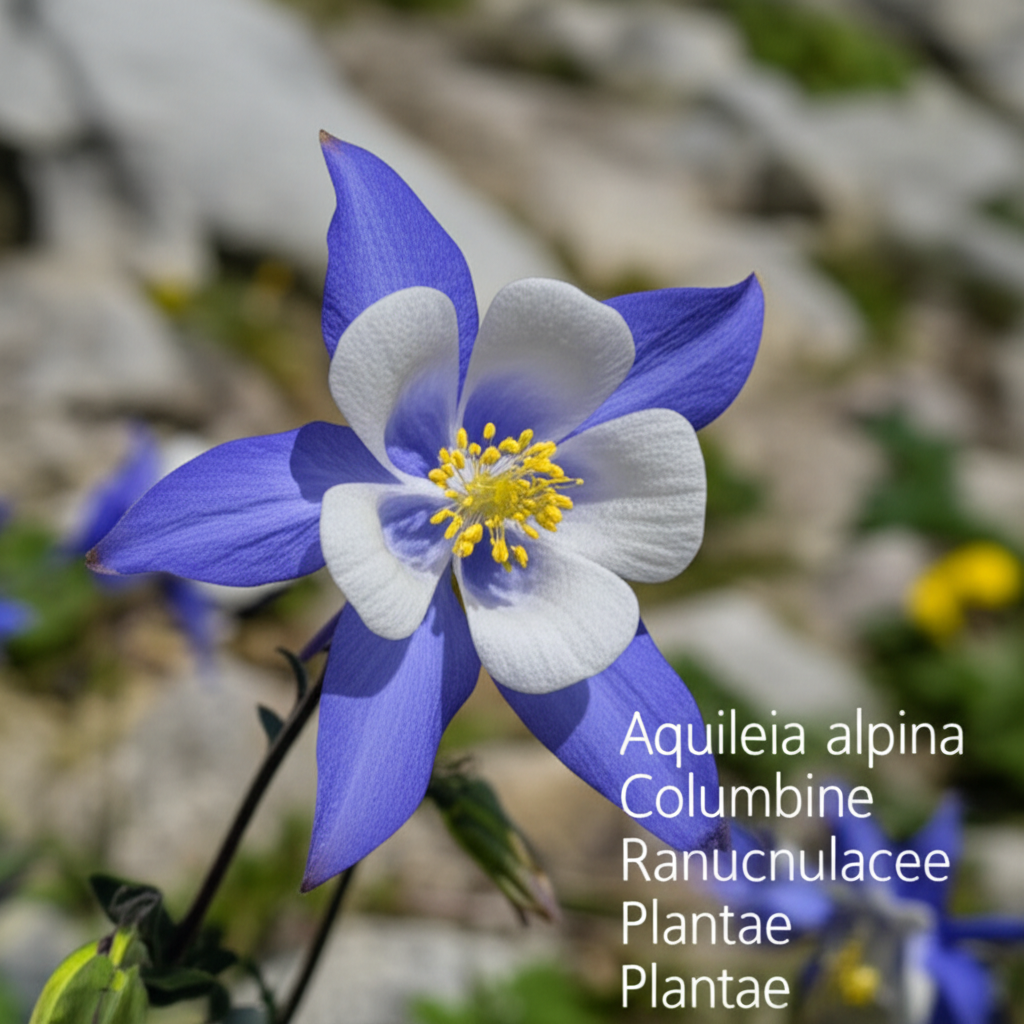

What is the Scientific Classification of Alpine Columbine and Why It’s Important in Gardening

The scientific classification of alpine columbine, Aquilegia alpina, is a fundamental aspect of understanding this plant’s origins, its natural habitat, and, consequently, its ideal growing conditions in your garden. Classification systems, like the Linnaean system, group organisms based on shared characteristics, tracing their evolutionary lineage. For Aquilegia alpina, its placement within the Ranunculaceae (buttercup) family and the Aquilegia genus tells us a great deal about its inherent traits.

Understanding its scientific classification is important in gardening because it provides a scientific basis for predicting a plant’s behavior, needs, and potential problems. For instance, knowing it’s an alpine species immediately flags its preference for cooler temperatures, well-drained soil, and often, exposure to bright light without intense, scorching heat. This biological blueprint helps gardeners make informed decisions about planting location, soil amendments, watering schedules, and even companion planting, ultimately leading to healthier, more successful cultivation of this stunning species. It moves us beyond guesswork to a more precise, science-backed approach to gardening.

Quick Recommendations or Key Insights about the Scientific Classification of Alpine Columbine

Genus Aquilegia: Indicates it belongs to the columbine family, known for its distinctive spurred flowers and a tendency towards woodland or alpine habitats.

Aquilegia alpina: Specifically identifies the species as native to alpine regions, suggesting a tolerance for cold, rocky environments, and potentially, a dislike for prolonged heat and humidity.

Ranunculaceae Family: Links it to the buttercup family, which often features vibrant flowers and can include plants with medicinal properties, but also some that may be toxic if ingested.

Alpine Origin: Crucial for understanding its environmental needs: bright light, cool temperatures, good drainage, and protection from harsh, drying winds.

Horticultural Implications: Guides choices for soil type (alkaline, well-drained), light exposure (partial shade in hot climates), and watering (consistent moisture, not waterlogged).

Detailed Breakdown of the Scientific Classification of Alpine Columbine

Botanical Classification: Placing Aquilegia alpina in the Plant Kingdom

The journey of understanding Aquilegia alpina begins with its place in the vast tapestry of the plant kingdom.

Kingdom: Plantae (Plants)

This is the broadest category, encompassing all photosynthetic organisms with cell walls made of cellulose.

Phylum: Tracheophyta (Vascular Plants)

This indicates that Aquilegia alpina possesses vascular tissues (xylem and phloem) for transporting water and nutrients, allowing it to grow taller and more complex than non-vascular plants like mosses.

Class: Magnoliopsida (Dicotyledons)

This signifies that the plant is a dicot. Key characteristics of dicots include having two seed leaves (cotyledons) in the embryo, net-like venation in their leaves, and flower parts typically in multiples of four or five.

Order: Ranunculales

This order groups families of plants that often have simple, unfussy floral structures, and many members are known for their attractive flowers.

Family: Ranunculaceae (Buttercup Family)

This is a large and diverse family of flowering plants. Members of the Ranunculaceae are known for their often showy flowers, which can have numerous stamens and pistils. Other common garden plants in this family include delphiniums, anemones, and clematis. Many Ranunculaceae species have historically been used in traditional medicine, but some can be toxic, so caution is advised.

Genus: Aquilegia (Columbines)

The genus Aquilegia is characterized by its unique, often spurred flowers, which are adapted for pollination by specific insects, historically thought to resemble an eagle’s talons (hence aquila, Latin for eagle). Columbines are found in temperate regions worldwide, with diverse species adapted to various habitats, from woodlands to alpine meadows.

Species: Aquilegia alpina

This specific epithet, alpina, directly refers to its native habitat: the Alps and other high mountain ranges of Europe. This species is renowned for its large, often deep blue to violet, nodding flowers, typically borne on sturdy stems. Its alpine origins are the most critical clue for gardeners attempting to replicate its ideal growing conditions.

Why This Classification Matters for Gardeners

The scientific classification isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s a practical guide for successful gardening.

Habitat Clues: Belonging to the Aquilegia genus tells us to expect flowers with spurs, likely adapted for specific pollinators. The alpina species epithet is a strong indicator of its need for cool conditions, good drainage, and exposure to bright light without extreme heat.

Soil Preferences: The Ranunculaceae family often thrives in soils that are rich but well-drained. Alpine plants, in particular, are adapted to rocky, lean soils, suggesting that while they appreciate some organic matter, excessive richness or waterlogging will be detrimental. They often prefer slightly alkaline conditions.

Light Requirements: Alpine environments are characterized by high light intensity but often filtered by clouds or clear mountain air, and crucially, cooler temperatures. This translates to a need for bright light, but protection from the harsh, direct sun of hot afternoons in lower altitudes and warmer climates.

Watering Needs: Plants adapted to alpine scree slopes or meadows typically experience periods of moisture followed by good drainage. They don’t like to sit in waterlogged soil, but they also don’t want to dry out completely during their growing season.

Hardiness: Its alpine origins indicate a plant well-suited to cold winters and likely to be hardy in many temperate zones, provided its other needs are met.

Quick Recommendations or Key Insights about the Scientific Classification of Alpine Columbine

Soil Drainage is Paramount: Mimic alpine conditions by ensuring your soil drains exceptionally well, even adding grit or gravel if necessary.

Cool Root Zone: Alpine plants dislike hot soil. Consider mulching or planting companion plants to keep their roots cool, especially in warmer climates.

Morning Sun, Afternoon Shade: This is the golden rule for Aquilegia alpina in most gardens, particularly those in warmer regions.

Avoid Over-Fertilizing: Rich, overly fertile soil can lead to weak, floppy growth and fewer flowers.

Pollinator Friendly: Like other columbines, Aquilegia alpina is attractive to long-tongued pollinators, such as bees and hawk moths, due to its spurred nectar spurs.

Detailed Breakdown of the Scientific Classification of Alpine Columbine

The Scientific Classification Explained in Detail

Let’s delve deeper into the taxonomic hierarchy:

Kingdom Plantae: This places Aquilegia alpina firmly within the world of flora, distinguishing it from animals, fungi, and bacteria. It signifies a complex organism that produces its own food through photosynthesis.

Phylum Tracheophyta: This means it has a vascular system, enabling efficient transport of water and nutrients. This is crucial for its ability to grow upright and support its foliage and blooms, differentiating it from mosses and liverworts.

Class Magnoliopsida (Dicotyledons): This classification highlights several key morphological traits. Dicot seeds contain two embryonic leaves (cotyledons), which provide nourishment to the seedling. Mature leaves typically exhibit a reticulate (net-like) pattern of veins. Flower parts are usually arranged in whorls of four or five. This class also includes many of the world’s most important food crops and ornamental plants.

Order Ranunculales: This order is part of the basal angiosperms, meaning it represents some of the earliest diverging lineages of flowering plants. Plants in this order often have primitive floral characteristics, such as numerous stamens and carpels, and their leaves can be simple or compound.

Family Ranunculaceae: This is a family of considerable horticultural importance. It’s characterized by typically herbaceous perennial plants, often with showy, showy flowers that may lack true petals but possess colorful sepals. The prominent spurs on columbine flowers are modified petals, a key feature of the Aquilegia genus within this family. The family also contains plants with a history of medicinal use, but it’s important to note that some members can be toxic if ingested due to the presence of protoanemonin.

Genus Aquilegia: This genus comprises about 60-70 species of herbaceous perennial plants, commonly known as columbines or Granny’s bonnets. The name Aquilegia derives from the Latin word aquila, meaning “eagle,” referring to the characteristic spurred petals that resemble an eagle’s talons. Columbines are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, with a significant concentration in North America and Eurasia. They are beloved for their intricate, delicate flowers and are often found in woodland clearings, meadows, and alpine environments.

Species Aquilegia alpina: This is the specific designation for the Alpine Columbine. It is native to the high mountain regions of Europe, particularly the Alps, but also found in the Pyrenees, Carpathians, and Balkans. Its natural habitat is typically alpine meadows, rocky slopes, and open woodlands at elevations ranging from 1,200 to 2,800 meters (approximately 3,900 to 9,200 feet). These conditions are characterized by:

Cool Temperatures: Extended periods of cold, frost, and snow cover.

Bright Light: High levels of sunlight, often unfiltered by dense canopies.

Well-Drained Soil: Rocky, often calcareous soils with excellent drainage, preventing waterlogging.

Protection from Extreme Heat: Absence of prolonged, scorching temperatures.

Wind Exposure: Often accustomed to moderate to strong winds, which can help prevent fungal diseases.

Scientific Perspective: Why “Alpine” Matters

The species epithet alpina is the most critical piece of information derived from its scientific classification for a gardener. It directly informs us about its natural environment and, by extension, its horticultural needs. Alpine plants are evolutionarily adapted to survive in harsh conditions:

1. Cold Tolerance: They have mechanisms to withstand freezing temperatures, often through dormancy and the production of antifreeze proteins.

2. Drought Resistance (at times): While they may grow in areas with snowmelt and summer rains, alpine soils drain rapidly. Plants develop ways to cope with periods of dryness, often with compact growth habits or specialized root systems.

3. High Light Intensity: Above the tree line, there is less atmospheric filtering of sunlight. Alpine plants are equipped to handle high UV radiation and intense light, provided it’s not accompanied by excessive heat.

4. Nutrient-Poor Soil: Alpine soils are typically thin, rocky, and low in organic matter. Plants adapted to these conditions are often efficient at nutrient uptake and do not require overly rich, heavily amended soil.

Practical Applications in the Garden

Understanding the scientific classification of Aquilegia alpina translates directly into practical gardening strategies:

Site Selection: Choose a location that receives ample bright light, especially morning sun, but offers protection from the intense afternoon sun in warmer climates. A north-facing slope or a spot near taller plants that cast afternoon shade is ideal.

Soil Preparation: Amend your garden soil with plenty of grit, coarse sand, or perlite to ensure excellent drainage. If your soil is heavy clay, consider raised beds or planting in containers with a well-draining alpine mix. While they appreciate some organic matter, avoid heavy compost applications. A slightly alkaline pH is generally preferred.

Watering Regimen: Water regularly, especially during dry spells, but allow the soil to dry out slightly between waterings. Ensure that water drains away freely. Avoid overhead watering late in the day, which can encourage fungal diseases.

Mulching: Use a layer of gravel, small stones, or composted bark mulch around the base of the plant. This helps retain soil moisture, suppresses weeds, keeps the roots cool, and mimics the rocky substrate of its natural habitat.

Companion Planting: Consider planting Aquilegia alpina with other hardy perennials that enjoy similar conditions, such as certain sedums, thyme, or low-growing rockery plants. These can also help shade the soil around the columbine’s roots.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Planting in Full, Hot Sun: While they can tolerate sun, prolonged exposure to intense, direct afternoon sun in hot climates will scorch the foliage and stress the plant, leading to reduced flowering and potential death.

Waterlogged Soil: This is perhaps the most common killer of alpine plants. Their roots need air, and constant wetness leads to root rot.

Over-Fertilizing: Feeding them with rich fertilizers can result in lush foliage but few flowers, and can make the plant susceptible to pests and diseases.

Too Much Shade: While afternoon shade is beneficial, complete shade will result in leggy growth and poor flowering.

Ignoring Drainage: Planting in heavy, compacted soil without amending for drainage is a recipe for disaster for this alpine specialist.

Expert Tips or Pro Insights

Propagate from Seed: Aquilegia alpina can be grown from seed, but stratification (a period of cold, moist conditions) is often required to break dormancy. Sow seeds in autumn or early spring and place the pots in a cold frame or unheated greenhouse.

Deadheading for Longevity: While not as crucial as for some annuals, deadheading spent flowers can prevent the plant from expending energy on seed production and may encourage a second, albeit smaller, flush of blooms. However, some gardeners prefer to leave the seed heads for their architectural interest and to allow natural self-seeding.

Pest and Disease Management: Healthy plants in the right conditions are less susceptible. Watch out for aphids, which can sometimes cluster on new growth. Powdery mildew can be an issue in humid conditions or if air circulation is poor, so ensure good spacing and avoid overhead watering late in the day.

Naturalizing: In suitable conditions, Aquilegia alpina can self-seed, creating a naturalistic drift of plants reminiscent of its alpine origins. Allow some seed heads to mature if you want this effect.

Replicating Alpine Conditions: Think about creating a “rock garden” effect. Plant on a slight slope, incorporate plenty of stone mulch, and select companions that also hail from cooler, well-drained environments.

Seasonal or Climate Considerations

Spring: This is typically when Aquilegia alpina emerges from dormancy and begins its active growth and flowering period. Ensure adequate moisture as the weather warms.

Summer: In cooler climates (e.g., UK, Pacific Northwest, Northern Europe), full sun might be manageable, but even here, afternoon shade is a bonus. In warmer climates (e.g., Mediterranean, hotter parts of the US), afternoon shade is essential to prevent heat stress. Consistent watering, but with excellent drainage, is key.

Autumn: The plant begins to die back. You can cut back the dead foliage or leave it for winter interest and to protect the crown. Seeds can be collected if desired.

Winter: Aquilegia alpina is fully hardy and benefits from a cold dormancy period. Ensure the soil doesn’t remain waterlogged during winter freeze-thaw cycles, as this can damage the roots.

Planting Zones: Generally hardy in USDA Zones 3-7. In Zone 8 and warmer, providing significant afternoon shade and very good drainage is absolutely critical.

Buying Guide or Decision-Making Process

When purchasing Aquilegia alpina:

1. Source: Look for reputable nurseries specializing in alpine or rock garden plants, or those known for hardy perennials. Online seed suppliers are also a good option if you’re prepared to start from scratch.

2. Plant Appearance: Choose plants that look healthy, with no signs of yellowing leaves, wilting, or visible pests. The foliage should be a vibrant green.

3. Pot Size: A plant in a 4-inch or 1-gallon pot is usually a good size for transplanting. Avoid plants that are severely root-bound.

4. Species Identification: Ensure you are buying Aquilegia alpina and not a hybrid or another columbine species, as their needs can vary. Look for descriptions that mention its alpine origins and characteristic blue/violet flowers.

5. Seed Viability: If buying seeds, check the harvest date and storage recommendations. Alpine columbine seeds often have a limited viable period and benefit from cold stratification.

FAQ Section for the Scientific Classification of Alpine Columbine

Q1: Is Aquilegia alpina a true alpine plant?

A1: Yes, as its species name alpina suggests, it is native to the high alpine regions of Europe, thriving in rocky, cool, and well-drained environments.

Q2: What does the Ranunculaceae family tell me about growing Aquilegia alpina*?

A2: Being in the buttercup family suggests it prefers well-drained soil, often slightly alkaline, and can be sensitive to waterlogging. It also indicates a potential for beautiful, intricate flowers typical of the family.

**Q3: Why is understanding its genus