Introduction: A Forest Floor Marvel

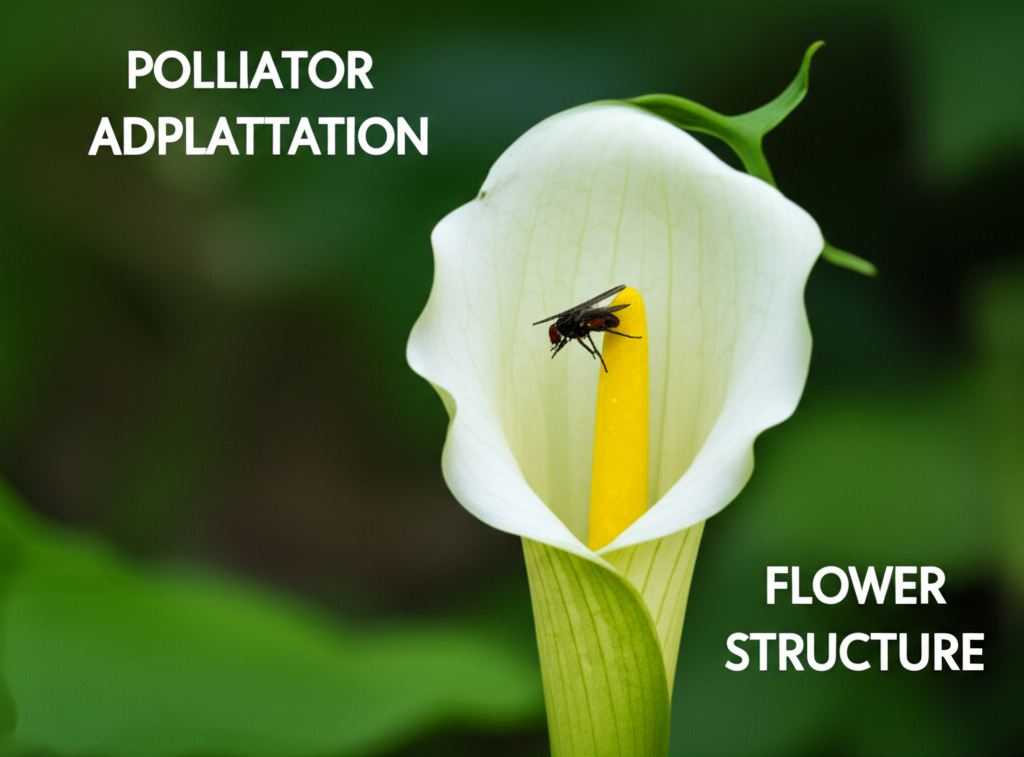

The Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum) is a captivating woodland wildflower found across eastern North America, instantly recognizable by its unique and somewhat bizarre floral structure. Often overlooked amidst the vibrant blooms of spring, this plant offers a masterclass in evolutionary adaptation, particularly in its intricate relationship with its pollinators. Its common name perfectly describes its appearance: a “Jack” (the spadix) rises from a “pulpit” (the spathe), creating a miniature, hooded enclosure that plays a critical role in the plant’s reproductive strategy. This article delves deep into the fascinating morphology of the Jack-in-the-Pulpit, dissecting its component parts and exploring the ingenious ways it has evolved to attract and facilitate pollination by its specialized visitors.

Deconstructing the Jack-in-the-Pulpit: A Botanical Breakdown

To understand the pollination adaptations of the Jack-in-the-Pulpit, it’s essential to first grasp its unique floral anatomy. Unlike many familiar flowers that present showy petals to attract pollinators, the Jack-in-the-Pulpit’s reproductive organs are concealed within a specialized structure.

The Spathe: The “Pulpit”

The most prominent feature of the Jack-in-the-Pulpit is the spathe. This is not a petal, but rather a modified leaf that forms a hood or canopy over the reproductive parts. The spathe is typically green, often streaked with purple or brown, and can vary in size and shape. It arches over the spadix, creating a protective chamber.

- Shape: Usually hooded, triangular, or helmet-shaped.

- Coloration: Predominantly green, often with distinctive purplish or brownish stripes or blotches.

- Texture: Smooth and somewhat leathery.

- Function: Primarily to enclose and protect the spadix and to guide pollinators.

The Spadix: The “Jack”

Emerging from the base of the spathe is the spadix, the central spike that bears the actual flowers. The spadix is typically club-shaped and can vary in length. It is often topped by a sterile appendage, a knob-like structure that can be prominent or reduced, and may be smooth or rough. The true flowers, which are small and inconspicuous, are located at the base of the spadix, hidden within the spathe.

- Shape: Elongated, club-shaped, tapering towards the tip.

- Color: Varies from greenish-yellow to dark purple or brown, often matching the spathe’s markings.

- Appendage: A sterile, often thickened tip that may be smooth or textured.

- Floral component: The base of the spadix hosts the minute male and female flowers.

The Inflorescence: A Hidden World

The entire reproductive structure of the Jack-in-the-Pulpit is technically an inflorescence, a cluster of flowers. The spathe and spadix are highly modified bracts and a modified spike, respectively, that enclose these tiny flowers. The male flowers are typically located above the female flowers on the spadix. The female flowers contain pistils capable of fertilization, while the male flowers contain stamens producing pollen.

The Ingenious Pollination Mechanism: A Trap and a Release

The Jack-in-the-Pulpit’s pollination strategy is a remarkable example of co-evolution, relying on small insects, primarily fungus gnats and thrips, for successful reproduction. The plant has evolved a sophisticated system to attract, trap, and ultimately facilitate the transfer of pollen.

Attracting Pollinators: The Scent and Subtle Cues

While not overtly fragrant in the way many flowers are, the Jack-in-the-Pulpit emits a subtle scent that attracts its target pollinators. This scent is thought to mimic the odor of decaying organic matter or fermenting substances, a perfect lure for fungus gnats, which are often found in damp, shaded environments where the Jack-in-the-Pulpit thrives. The visual cues of the spathe, with its intriguing coloration, also play a role in attracting insects.

The Pitfall Trap: A One-Way Journey

Once an insect, enticed by the scent, enters the spathe, it finds itself in a cleverly designed pitfall trap. The interior walls of the spathe are lined with downward-pointing stiff hairs. These hairs act like a one-way barrier, allowing insects to easily descend into the chamber at the base of the spadix where the pollen-bearing male flowers are located, but making it incredibly difficult for them to climb back out.

Trapped and Pollinating: A Forced Encounter

Inside the spathe, the insect is essentially trapped. As it moves around in its confined space, it comes into contact with the pollen from the male flowers at the top of the spadix. If the insect has visited another Jack-in-the-Pulpit previously, it will also deposit pollen onto the stigma of the female flowers located lower on the spadix.

The Escape Route: A Release Mechanism

After spending some time within the spathe, the insect’s chances of escape increase. The downward-pointing hairs on the spathe eventually wither or become less rigid, allowing the insect to fly upwards and out of the opening. This mechanism ensures that the insect has had ample opportunity to pollinate the female flowers before it makes its exit, carrying pollen to the next Jack-in-the-Pulpit it visits. The timing of this hair senescence is crucial for the plant’s reproductive success.

Key Facts and Comparisons

Understanding the Jack-in-the-Pulpit’s adaptations is easier when placed in context. Here’s a comparison with other flowering plants and a summary of key characteristics.

| Feature | Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum) | Typical Showy Flower (e.g., Tulip) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Attractant | Subtle scent (mimicking decay), visual cues (spathe coloration) | Bright petals, strong fragrance |

| Reproductive Structures | Spadix (bearing flowers) enclosed by spathe (modified leaf) | Petals, sepals, stamens, pistil openly displayed |

| Pollination Mechanism | Pitfall trap with downward-pointing hairs, controlled release | Direct access for pollinators to nectar and pollen |

| Primary Pollinators | Fungus gnats, thrips | Bees, butterflies, hummingbirds |

| Flowering Season | Spring (April-June) | Varies by species (spring, summer, fall) |

| Habitat | Shaded, moist woodlands, swamps, stream banks | Varies widely (gardens, meadows, forests) |

Pollinator Interactions: A Delicate Dance

The relationship between the Jack-in-the-Pulpit and its pollinators is a testament to the intricate web of life in forest ecosystems.

The Role of Fungus Gnats

Fungus gnats (Diptera: Sciaridae, Mycetophilidae) are the primary architects of the Jack-in-the-Pulpit’s reproductive success. These small, delicate flies are attracted to the plant’s scent, which can signal the presence of suitable breeding sites or food sources. Once inside the spathe, they become trapped and, in their struggle to escape, facilitate pollination.

Other Insect Visitors

While fungus gnats are the most frequent visitors, other small insects, such as thrips and occasionally small beetles, may also enter the spathe. Their role in pollination is likely secondary, but they contribute to the overall insect activity within the enclosure.

Avoiding Unwanted Visitors

The Jack-in-the-Pulpit’s pollination system is highly specialized. Larger insects or those that do not respond to the specific scent cues are generally excluded from entering the spathe. This selectivity ensures that only the most effective pollinators interact with the reproductive organs.

The Life Cycle and Seed Dispersal

Following successful pollination, the Jack-in-the-Pulpit enters its fruiting stage.

The Fruit: A Cluster of Berries

The female flowers, once pollinated, develop into bright red berries that cluster together on the spadix. These berries are attractive to birds and other small animals, which consume them and disperse the seeds through their droppings. This is a more conventional method of seed dispersal, contrasting with the specialized pollination strategy.

Seed Germination and Growth

Jack-in-the-Pulpit seeds require stratification (a period of cold, moist conditions) to germinate. Once sprouted, the seedlings develop slowly, often taking several years to reach maturity and produce their first flowers. The plant is herbaceous and dies back to its underground corm each winter.

Adaptations in Different Species and Climates

While Arisaema triphyllum is the most common species in North America, the genus Arisaema is diverse, with over 150 species found primarily in tropical and temperate Asia and Africa. These species exhibit variations in their spathe and spadix morphology, often reflecting adaptations to different pollinator guilds and environmental conditions. For instance, some species may have more elaborate spathe appendages or different scent profiles to attract a wider range of insects or even beetles.

Conservation and Ecological Significance

The Jack-in-the-Pulpit plays an important role in its native woodland ecosystem. It provides food for insects and serves as a food source for animals that disperse its seeds. Its presence is an indicator of healthy, undisturbed forest environments. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to human activities can threaten populations of this unique plant and its associated pollinator communities.

Summary of Pollination Process and Adaptations

The Jack-in-the-Pulpit’s reproductive success is a marvel of natural engineering. Its entire floral structure is geared towards a specific type of pollination, showcasing remarkable adaptations.

| Step/Aspect | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scent Attraction | Emits a scent mimicking decay to attract fungus gnats and thrips. | Effectively lures specialized pollinators in dark, humid environments. | May not attract a wide variety of pollinators. |

| Spathe as a Hood | Modified leaf encloses the spadix and reproductive organs. | Protects flowers from the elements and unwanted visitors. Creates a contained environment. | Limits visibility of reproductive parts. |

| Pitfall Trap Mechanism | Downward-pointing stiff hairs inside the spathe prevent easy escape. | Ensures pollinators remain trapped long enough for pollen transfer. Maximizes contact with floral structures. | Can lead to pollinator mortality if escape is permanently blocked. |

| Controlled Release | Hairs eventually wither, allowing trapped insects to escape upwards. | Facilitates pollen dispersal to other plants. Prevents complete annihilation of pollinator populations. | Timing is critical; a delay can be detrimental. |

| Specialized Pollinators | Relies on specific small insects like fungus gnats. | High degree of pollination efficiency from well-adapted visitors. | Vulnerability if the specific pollinator population declines. |

| Energy Investment | Less energy spent on showy petals compared to many other flowers. | Resources can be directed towards other parts of the plant, such as underground storage organs. | Relies on specific environmental conditions to attract pollinators. |

Conclusion: A Masterpiece of Evolutionary Ingenuity

The Jack-in-the-Pulpit stands as a compelling example of how plants have evolved sophisticated strategies to ensure their reproductive success. Its unique spathe and spadix structure, combined with a deceptive scent and a clever pitfall trap mechanism, are perfectly tailored to attract and utilize its primary pollinators, the fungus gnats. This intricate adaptation highlights the power of natural selection and the delicate balance of relationships within our natural world. Observing this enigmatic wildflower offers a glimpse into the fascinating, often hidden, drama of plant reproduction and the vital role of pollinators in sustaining biodiversity.